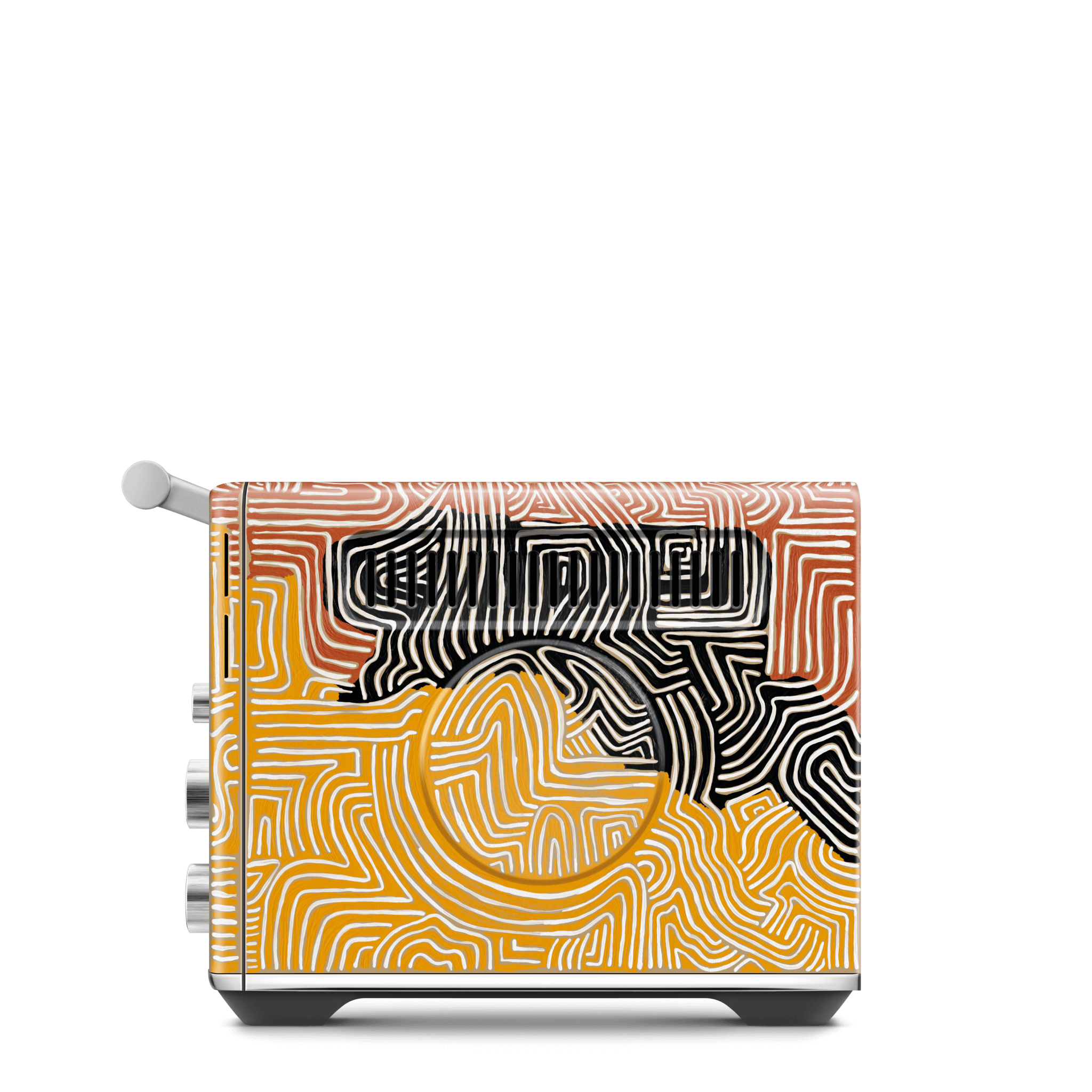

In Aboriginal culture, bread making has very little to do with combining flour and water. It’s about the stories and jokes shared while making it that makes it taste good.

The Aboriginal connection to home is also about how we care for the land. Our traditional methods of cultivating grain are not just about the nourishment of bodies, but the nourishment of the land, too. Kangaroo and wallaby grasses have been cultivated on this ancient land for 65,000 years. They are gluten-free and grown without irrigation and pesticides.

Historically and today, breaking bread is all about the connections we have with the people and places we love.

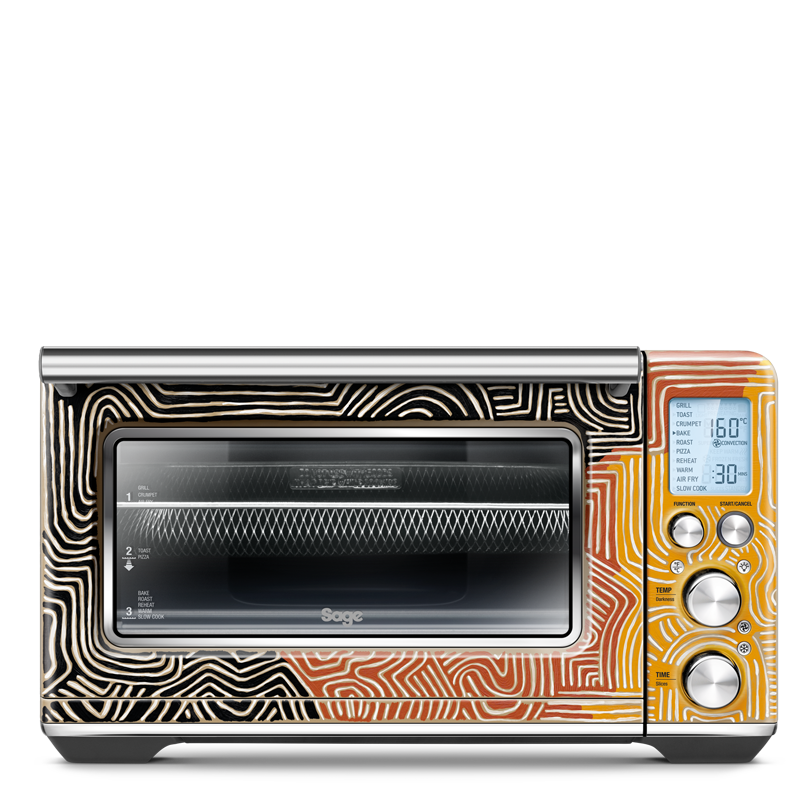

Dhuuyaay connects to one of the many roles of the Yuwaalaraay women as the carers for dhuuyaay (fire stick farming), a tool used in ceremonial season and in everyday life. It depicts the role of fire in shaping and sustaining country and maintaining balance in the natural world.

For Aboriginal people the presence of native grasses across the landscape indicates the health of country, and large grasslands were maintained meticulously through cool burns or fire stick farming, which would both maintain balance and stimulate new growth. These practices were fine-tuned over many hundreds of generations, with many Aboriginal communities continuing these practices across Australia today, with a recent revival in some areas which acknowledge the sophistication of this ancient practice and its relevance today.

Fire stick farming is a sophisticated example of how the traditional Aboriginal knowledge and agricultural practices directly increased the food supply for their people and local native animals by promoting the growth of edible ground-level plants. This traditional knowledge is now being exported across the world to manage land in countries including Argentina and Namibia.